7th Street and the West Coast Blues Walk of Fame

For several decades 7th Street was a hub of commercial and cultural life in West Oakland. As one of the city’s first districts, West Oakland began as a multicultural community. As the city expanded its border, and Whites, who could afford to, moved out to other areas of town, West Oakland became a predominantly African American community, peaking during World War II. Racial covenants, discriminatory lending and renting, and the proximity of industrial jobs kept African Americans in the district.

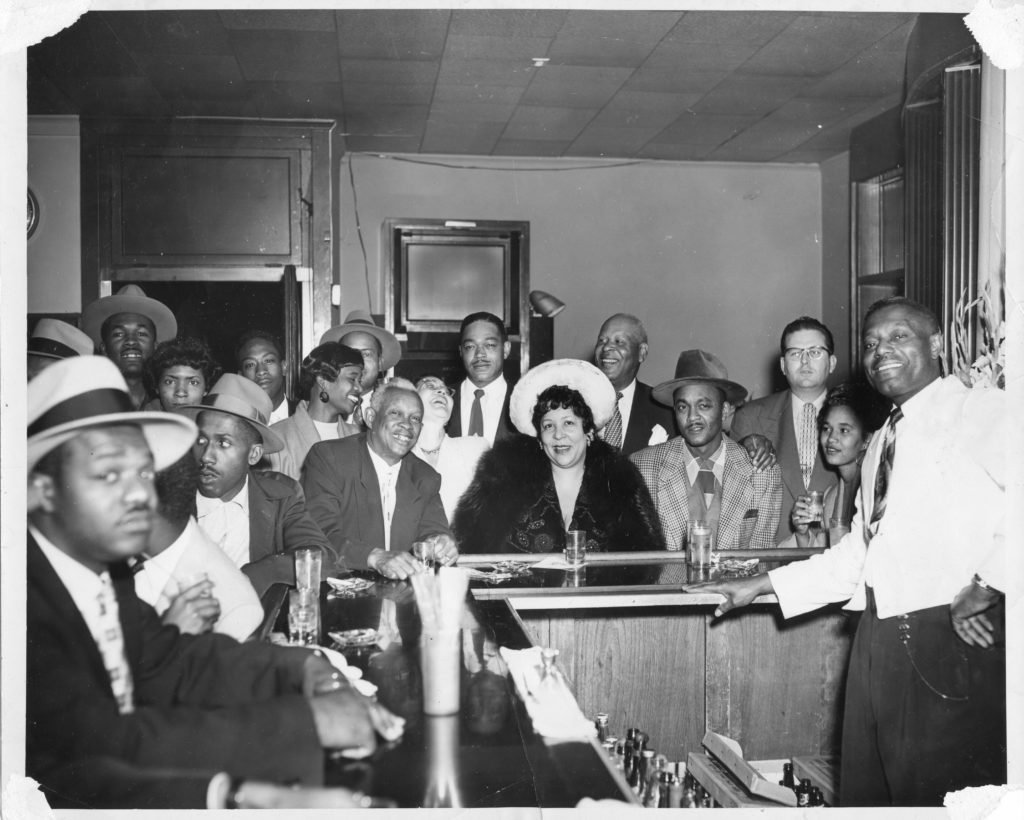

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Southern Pacific Railroad was the chief employer of African Americans in Oakland. Two of the company’s rules impacted the demographics of West Oakland: 1) that Pullman porters, redcaps and maids be African American, and 2) that they must live west of Adeline Street to be near the 16th Street train depot in case they were called to work. These corporate policies helped transform West Oakland into an African American enclave. As rail workers were paid comparatively more than other African Americans working as domestics, agricultural workers, or unskilled laborers, they were able to develop and sustain a viable Black middle class. Along busy 7th Street, where streetcars rumbled, there were banks, clothing stores, real estate offices, pawn shops, grocery stores, and nightclubs like Esther’s Orbit Room and Slim Jenkins’ Supper Club.

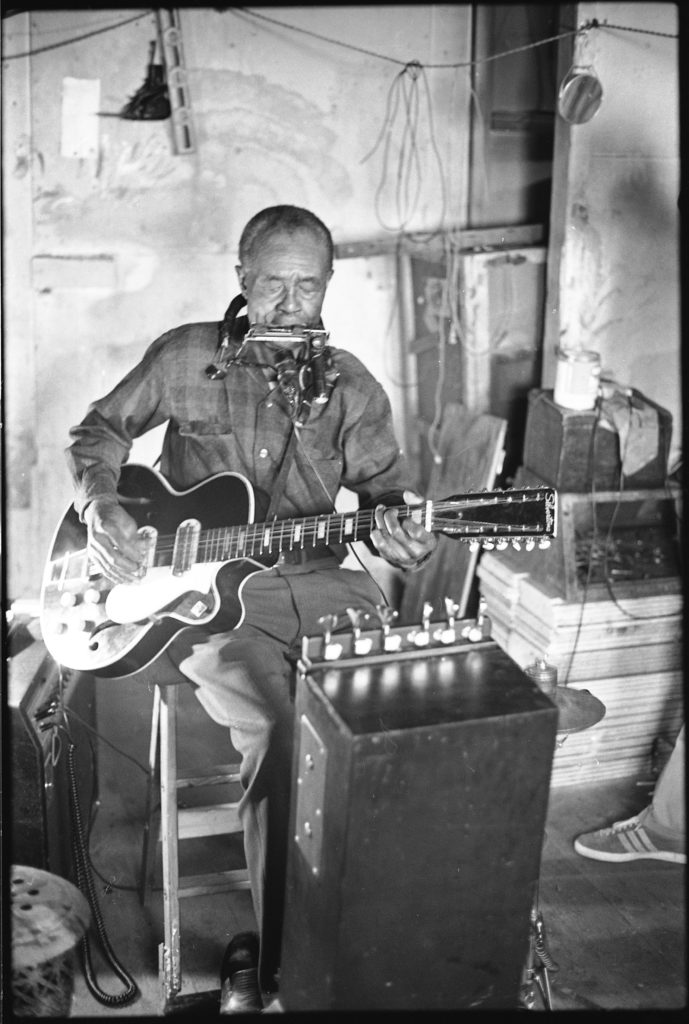

The Great Migration (1919-1970) of African Americans out of the segregated, oppressive South led to an amalgam of cultural and musical traditions that would give West Oakland a distinctive feel and sound. From 1940, the African American population of Oakland grew exponentially from 8,452 to 47,562 by 1950. Musicians from Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma came and created what was called “mutt music,” according to blues historian and guitarist Ronnie Stewart. Musicians took a little bit from everywhere, creating a unique Oakland brand of blues which, unlike other Blues styles, included a horn section. The district was such an active, hotbed of creativity and performance, that it was nicknamed the “Harlem of the West.” Top musicians like B.B. King, Lowell Fulson, Bobby Bland, Etta James, James Brown, and Jimmy McCracklin played clubs along 7th Street.

From 1959 to 1970 various redevelopment plans changed the landscape, population, and spirit of West Oakland. The double-decker Cypress Structure (an extension of the Nimitz/880 freeway), the construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system, and the new Post Office Processing and Distribution Center Almost 5,000 families were displaced, more than 800 businesses shut down, and about 2,500 Victorian homes were razed, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. From the late 1950s through the 1960s, West Oakland’s population fell by 20%. When city leaders and BART administrators decided to end the undergrounding of the BART tracks, and have the trains come out above ground through West Oakland, it marked the death knell of the once-vibrant 7th Street. Noise, construction blockades, dirt, and displacement greatly impacted the access to and vibrancy of the 7th Street corridor. The nightclubs that had drawn many top musical acts to the area were eventually shuttered but the culture did not die.

Ronnie Stewart is the executive director of the West Coast Blues Society (formerly the Bay Area Blues Society). This group sponsors the Blues Walk of Fame, an 84-plaque tribute to the musicians, music producers, and club owners who created and contributed to the Oakland blues scene. The Walk of Fame is located along 7th Street near the West Oakland BART station.

Listen to an interview with Ronnie Stewart, executive director of the West Coast Blues Society:

Voices of the People:

Listen to Oakland neighbors talk about what they love about their communities, the changes they’ve seen, what they envision for the future of Oakland and ideas on how to get there.

Photos by Bob White